http://artofmanliness.com/2012/07/12/the-generations-of-men-how-the-cycles-of-history-have-shaped-your-values-your-place-in-the-world-and-your-idea-of-manhood/?utm_source=Daily+Subscribers&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=800165ccee-RSS_EMAIL_CAMPAIGN/

The Generations of Men: How the Cycles of History Shape Your Values, Your Idea of Manhood, and Your Future

Image via capitalist_b

As is the generation of leaves, so to of men:

At one time the wind shakes the leaves to the ground

but then the flourishing woods

Gives birth, and the season of spring comes

into existence;

So it is with the generations of men, which

alternately come forth and pass away.

- Homer, The Illiad, Book Six

If you’ve been following AoM for awhile now, you know that Kate and I love history. I studied classical history in college and Kate actually taught American history and Humanities at a community college here in town. And in running the Art of Manliness for the past five years, we’ve read hundreds of old writings while researching material for our posts and two books.

Through our study and reading, something that we’ve both come to appreciate about history is just how right the author of Ecclesiastes was: “What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.”

We are often struck, even sort of tickled, about how much the hopes, observations, and complaints of people decades, even centuries, ago sound just like the hopes, observations, and complaints of modern folks. It’s uncanny sometimes!

It is often said that history repeats itself. But do these repetitions happen at random…or is some kind of regular cycle at work?

The Strauss-Howe Generational Theory

“All human things are a circle.” -Inscription upon the temple at Athens

While modern societies typically see history as a linear movement–either ever improving or declining from a past high–ancient and traditional cultures believed time was cyclical, just like the waxing and waning of the moon, the rising and setting of the sun, the birth and death of living creatures, the planting and harvesting of crops, and the seasons of the year. The idea of sacred time as an eternal round and the symbol of the ring or wheel is common to many faiths, including Buddhism and Hinduism. The Old Testament is in many ways the story of a “pride cycle” with repeating periods of renewal, regression, and repentance. And many ancients couldn’t help but notice that times of war and peace seemed to move in a regular cycle as well.

In the 1990′s, William Strauss and Neil Howe published two books, Generations and The Fourth Turning, which set out a bold and fascinating theory: that the generations of history change in a regular cycle, just like the seasons of the year — that the ancients were on to something with their cyclical view of time after all.

Strauss and Howe argue that the last five centuries of Anglo-American history can be explained by the existence of four generational archetypes that repeat sequentially in a fixed pattern every 80-100 years, the length of a long human life, or what the ancients called a “saeculum.” These generational archetypes are: Prophet, Nomad, Hero, and Artist. Each generation consists of those born during a roughly 20 year period. As each generation moves up the ladder of age and takes a different place in society, the mood of the culture greatly changes:

Childhood: 0-20 years old

Young Adulthood: 21-41

Midlife: 42-62

Elderhood: 63-83

Late Elderhood: 84+

Young Adulthood: 21-41

Midlife: 42-62

Elderhood: 63-83

Late Elderhood: 84+

A generation reaches it apex of influence when it moves into midlife and begins to take leadership positions of power within society. Thus every 20 years as a new generation fills the midlife rung of the age ladder, and the generation that previously occupied that rung moves into less influential elderhood, the mood of the culture shifts. As each generation type is born, matures, comes to influence in the culture, and then declines and dies, it plays a role in propeling society through a cycle of growth, maturation, entropy, destruction, and then regrowth. Just as in nature, this cycle of death and rebirth is necessary to maintain the health of the ecosystem or society.

Why do the same four generational archetypes repeat in the same way each saeculum? They are molded by four historical turnings that reoccur every 80-100 years as well. The four historical turnings are: High (First Turning), Awakening (Second Turning), Unraveling (Third Turning), and Crisis (Fourth Turning). Historical turnings and generational archetypes work together to power the generational cycles. Historical turnings shape generations in childhood and young adulthood; then, as parents and leaders in midlife and old age, generations in turn shape history.

Because each of the four generation types experience the four historical turnings at different times in their lives, each generation is shaped differently by these watershed moments in history.

Below I include a chart that lists the four generational archetypes and turnings and shows at which point in life each generation experiences the turnings:

| Prophet | Nomad | Hero | Artist | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Childhood | Elderhood | Midlife | Young Adult |

| Awakening | Young Adult | Childhood | Elderhood | Midlife |

| Unraveling | Midlife | Young Adult | Childhood | Elderhood |

| Crisis | Elderhood | Midlife | Young Adult | Childhood |

Each horizontal row represents a “generational constellation” — the set arrangement of the generations on the age ladder during a turning. The generational constellations are the same in each turning, saeculum after saeculum.

If you’re feeling confused, hopefully things will become clearer as we discuss the Historical Turnings and the Four Generational Types below. The theory will be easiest to grasp and keep track of if you think in terms of who the generational types were/are during our most recent saeculum as we go along:

Most Recent Generations:

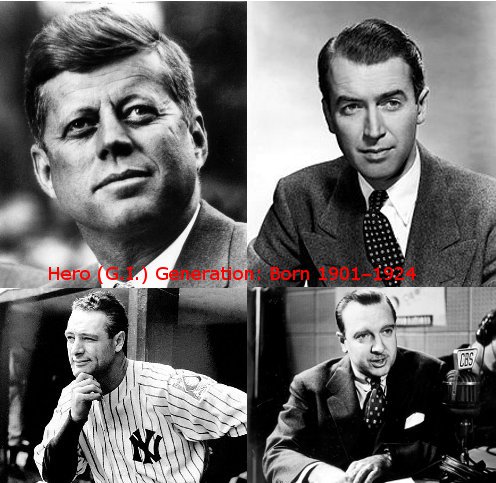

Heroes: G.I. Generation (born 1901-1924)

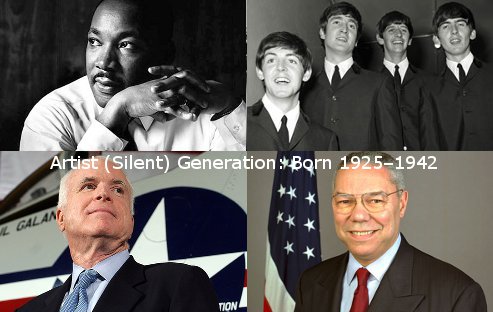

Artists: Silent Generation (born 1925–1942)

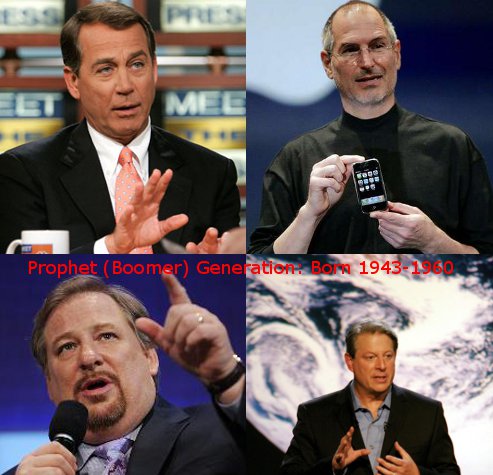

Prophets: Baby Boom Generation (born 1943-1960)

Nomads: Generation X (born 1961-1981)

Next Heroes: Millennial Generation (born 1982-2004)

Artists: Silent Generation (born 1925–1942)

Prophets: Baby Boom Generation (born 1943-1960)

Nomads: Generation X (born 1961-1981)

Next Heroes: Millennial Generation (born 1982-2004)

Most Recent Turnings:

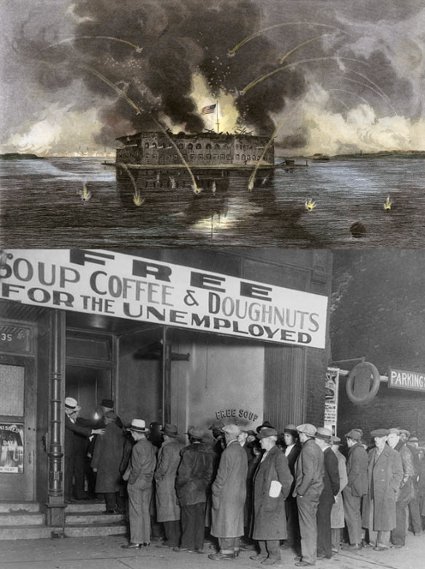

Crisis (Fourth Turning): Great Depression/WWII (1925-1945)

High (First Turning): Postwar Boom (1946-1960)

Awakening (Second Turning): Consciousness Revolution (1961-1981)

Unraveling (Third Turning): Reagan Revolution/Culture Wars (1982-2006)

Next Crisis (Fourth Turning): ? (2008-?)

High (First Turning): Postwar Boom (1946-1960)

Awakening (Second Turning): Consciousness Revolution (1961-1981)

Unraveling (Third Turning): Reagan Revolution/Culture Wars (1982-2006)

Next Crisis (Fourth Turning): ? (2008-?)

Before we move on, we should note that a cyclical view of history does not preclude the idea of a society progressing or regressing; the cycle may be spiraling up or spiraling down.

Historical Turnings

The saeculum is broken up into four periods: First Turning (High), Second Turning (Awakening), Third Turning (Unraveling), Fourth Turning (Crisis). Each lasts roughly 20 years, just as the generations do. It’s helpful to imagine these periods as the seasons of the year. The Awakening is the summer of the saeculum, and the Crisis is the winter. The Unraveling (fall) and High (spring) are the transitional seasons. An Awakening changes a society’s culture; a Crisis changes its public life.

The changing of the turnings always catches people by surprise, as people ever suppose that life will keep going on just like it is now. For example, people in the 1950s envisioned the future as a stretch of unceasing progress–a clean, orderly world filled wondrous technology and space travel. What they got instead was a sagging economy and the counter-culture movement. We are bad at seeing the next Turning coming because just as in nature, “the season that is about to come is always farthest removed from memory.” In nature we are currently in summer and are awaiting the fall–the season we have not experienced in the longest time; in history, we now await (or perhaps are actually in) the Crisis, the Turning we have not experienced since WWII.

High (First Turning)

A High follows the Crisis era. It is a time with strong civic values: institutions are strong and individualism is weak. Ideals that were valued during a crisis are institutionalized. The emphasis during a High is on planning and building–doing big things. Society is confident about where it wants to go collectively, though those outside the majority often feel stifled by the conformity. Culture is friendly, but bland and lacks spiritual depth. Big technological advances are often made during High eras. The amount of structure/protection/nurturing given children begins to diminish towards the end of the turning.

During a High, Old Prophets die off, Nomads enter elderhood, Heroes enter midlife, Artists enter young adulthood—and a new generation of Prophets is born.

The postwar boom between 1948 and 1963 was America’s most recent High. Before that was the twenty year period after the Revolutionary War. According to Strauss and Howe, the Civil War created an anomaly in which the High period was skipped.

Awakening (Second Turning)

The focus of society shifts from building institutions to developing an individual’s inner life. New social ideals emerge during this time and experimentation with utopian communities is common. Members of the coming-of-age Prophet generation are often at the forefront of the spiritual awakenings during Second Turning eras. Young activists look back at the previous High as a period of cultural and spiritual poverty and begin to rebel against the midlife Hero generation who made it possible. The amount of structure/protection/nurturing given children reaches a saeculum low.

During an Awakening, Old Nomads disappear, Heroes enter elderhood, Artists enter midlife, Prophets enter young adulthood—and a new generation of child Nomads is born.

The Consciousness Revolution of the 1960s, the Transcendental Movement, and theGreat Awakenings of the 18th and 19th centuries are examples of Awakening turnings.

Unraveling (Third Turning)

An Unraveling begins as a society embraces the liberating cultural forces set loose by the Awakening. Individualism and personal satisfaction are at their highest, while community and confidence in public institutions are at their lowest. Pleasure seeking and extreme lifestyles emerge. Society fragments into polarizing groups which makes decisive public action difficult. Instead of addressing problems, businesses and government leaders just kick the can down the road. Confidence in society’s future darkens, and the culture feels used up and worn out. Civic and moral paralysis and apathy set in. Art reflects the growing pessimism as themes of dreary realism take center stage. Child-rearing begins to move back towards protection and structure.

During Unravelings, Old Heroes disappear, Artists enter elderhood, Prophets enter midlife, Nomads enter young adulthood—and a new generation of child Heroes is born.

Previous Unravelings occurred around World War I and the decades before the Civil and Revolutionary Wars. According to Strauss and Howe, the most recent Unraveling began during the second term of the Reagan administration and continued into the 2000′s.Today trust in institutions and leaders are at an all-time low and individualism is at an all-time high. Decisions on national problems like the growing deficit, deteriorating infrastructure, and rising education and healthcare costs are continually postponed because politicians and citizens are increasingly entrenched in their ideologies; consensus action and progress seems impossible.

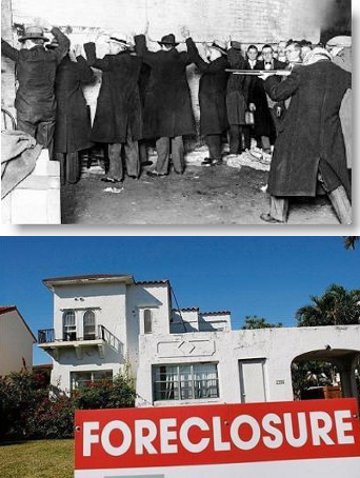

Crisis (Fourth Turning)

This is an era in which America’s institutional life is destroyed and rebuilt in response to a perceived threat to the nation’s survival. This threat can take numerous forms; economic distress caused by defaulting on national debt, hyper inflation, or widespread unemployment, social distress caused by class or race warfare, ecological distress caused by natural or man-made disasters, energy or water shortages, disease epidemics, secessionism and civil revolts, and traditional, nuclear, or cyber warfare are some of the possibilities. The Crisis can be caused by one large threat, or by the many little things that a society failed to deal with during the Unraveling finally coming to a head.

Obviously, societies’ are faced with wars and crises all the time; it is how the society responds to the crisis that determines whether it catalyzes into a Fourth Turning. There are always sparks, but not all sparks turn into fire. A spark ignites a Fourth Turning because in some way, the society is ready for it and wants it, though not consciously; they sense that society feels tired,worn out, and needs to be renewed.

No matter what form the Crisis takes, it galvanizes people into an action-taking consensus; problems that were once kicked down the road during the Unraveling are finally taken by the horns. Civic authority revives, cultural expression redirects towards community purpose, and people begin to locate themselves as members of a larger group. Self-sacrifice, institution building, and consensus replace self-interest, personal development, and contrarianism as values society encourages. Wanting to protect their children from the turmoil surrounding them, parents are overprotective of their children during the Crisis.

During the Crisis, Old Artists disappear, Prophets enter elderhood, Nomads enter midlife, Heroes enter young adulthood—and a new generation of child Artists is born.

America experienced a Crisis-era during the Revolutionary and Civil Wars. Our previous Crisis began with the Great Depression and ended after WWII. When Strauss and Howe wrote The Fourth Turning in 1997, they predicted that the next Crisis would begin in the middle of 00′s and last until around 2025. According to Howe’s current blog, he believes the next Fourth Turning began with the 2008 economic crisis.

Strauss and Howe argue that it’s never possible to predict how long or severe a Fourth Turning may be, or what form it may take (the last Crisis after all started with the Depression and ended with a World War). In whatever form it takes, by the time the Fourth Turning is over, it has created a sharp break with the old order and a rebirth and renewal of society — a new High.

Generational Archetypes

Just as there are four turnings in a saeculum, there are four generational archetypes: Prophet, Nomad, Hero, Artist. The generations are shaped both by each other and by the turnings; they are affected by the amount of nurturing they receive growing up and then by the challenges they face as they come of age.

The idea of breaking people into generations isn’t very popular in our highly individualized age. But to say that generations share common characteristics is not to say these cycles force people’s behavior, or that there are not always exceptions to the rule: in every generation there are three groups of people: those who set the tone for the generation, those who follow the tone-setters lead, and those who rebel against the generational mood altogether. Talking about generations is simply a way to acknowledge that because different age groups are raised in less or more nurturing families, and experience historical events at different times in their development, their “generational persona”–their “attitudes on family life, gender roles, institutions, politics, religion, lifestyle, and the future” are shaped in a distinct way.

It’s also important to keep in mind that no generation is “better” or “worse” than another; each generation has unique strengths and weaknesses, each is important, and each provides balance and self-correction to the cycle of history. This is especially important to remember as you notice that one of the generations is labeled the “Hero” generation. This is not in reference to its superiority, but to the fact, as you will see below, that the Hero generation serves as the foot soldiers during a Crisis, and so are given a chance to do heroic things during that time and are thus reverently remembered for their service during the Crisis. But the Hero generation has flaws and strengths just like every other.

Finally, it is essential to understand that just because generational types repeat throughout history, this does not mean they are just like each other. The Puritan generation and the Baby Boomer generation are both Prophet generations, but they couldn’t be more different! Instead, it is only that a set of salient characteristics unique to each generational archetype reemerges over and over again, manifesting in very different ways according to the circumstances of the time. So what the Puritans and Baby Boomers have in common is the value those generations placed on one’s inner convictions and spiritual awakening.

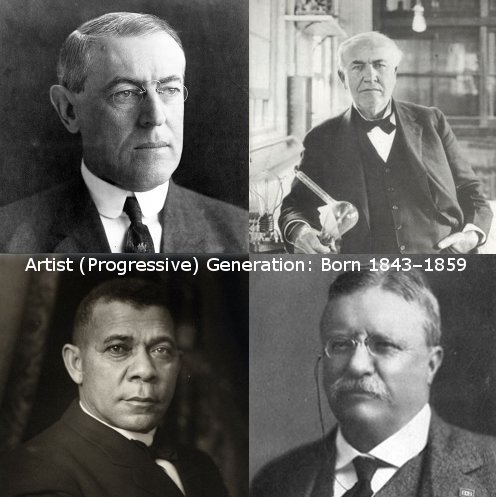

Artist

Artists grow up overprotected by adults during a Crisis. Children are expected to stay out of the way and be well behaved, and for the most part Artist children comply. Taught from a young age to please adults, Artists enter adulthood as one of the most conformist but also most well-off youth generations. Young adult Artists often take a supportive role to midlife Heroes. Those who find their generation’s conformity to elder expectations stifling, begin to explore a “fresher, more fulfilling role.” Rebellious young adult Artists are frequently the leaders of youth movements filled with teenage Prophets (like MLK).

In midlife, Artists become known for their flexible, consensus-building leadership. They put a premium on expertise, process, and statistics. While this allows Artists to take on complex issues in a nuanced way, midlife Artist leaders often get bogged down in details and tend to postpone unpleasant choices. Midlife Artists become increasingly sympathetic to and even embrace the ethos of the younger Prophet generation who led the Awakening Turning. Midlife Artists redefine what it means to age and try to remain young at heart.

In old age, Artists maintain their flexible attitude towards life and continue to adopt the values of the younger Prophet generation. “They preserve a social conscience, show a resilient spirit, and never stop raising new questions.”

In many ways, the Artist generation comes of age in an tough, in-between spot in the generational cycle; for example, the Silent Generation just missed out on serving in WWII, and were left only to hear the stories of service from the Hero generation, and then when the counter-cultural movement happened in the 60s and 70s, they were already settled down in families, leaving some to look on enviously at the Prophet generation’s experiments with drugs and free love. Because of their in-between position in history, members of the Silent Generation have sometimes been overlooked; there has never been a Silent Generation president, and because McCain lost the 2008 election, there almost certainly never will be.

The Artist generation’s main societal contributions are in the area of expertise and due process. The Artists generation produces, surprise, surprise, great artists (Elvis Presley, Andy Warhol), reformers (Theodore Roosevelt, Martin Luther King, Jr., John Dewey), and statisticians (Frederick Winslow Taylor). America has had four Artist Generations: Enlightenment Generation (1674–1700), Compromise Generation (1767–1791), Progressive Generation (1843–1859), and Silent Generation (1925–1942).

Prophet

Prophet generations are born after a Crisis Turning, and grow up increasingly indulged as children and youth, which imparts a sense of narcissism to this generation. They come of age as passionate young crusaders during an Awakening era and rebel against their elders’ spiritually sterile society. Self-discovery and authenticity are valued by Prophets throughout their lives, and they feel passionate about the morals, principles, and ideas they hold dear.

Prophets enter mid-life during an Unraveling by initially disengaging from public life in order to focus on themselves. However, slowly but surely, midlife Prophets begin to take on the mantle of leadership. Unlike Hero leaders who put action over ideals, Prophet leaders put ideals ahead of action. Because of this, irreconcilable rifts occur between Prophet factions, which causes societal problems to come to a head during an Unraveling.

Prophets reach elderhood during a Crisis. By then, one of the competing Prophet factions from the Unraveling prevails which sets the agenda and tone for public action during the Crisis. During the Crisis, elder Prophets provide moral vision and values-oriented leadership to younger generations. They inspire younger generations to sacrifice, although during their own youths they were generally not “in the trenches,” themselves, and are thus ultimately remembered more for their words than their actions. They may lead society through the Crisis to the birth of a new High….or, if they do not lead well, to destruction.

The Prophet Generation’s main societal contributions are vision, values, and religion. They often produce America’s most notable preachers, activists, radicals, and writers. Prophet Generations include: Puritan Generation (1588–1617), Awakening Generation (1701–1723), Transcendental Generation (1792–1821), Missionary Generation (1860–1882), and Boomer Generation (1943-1960).

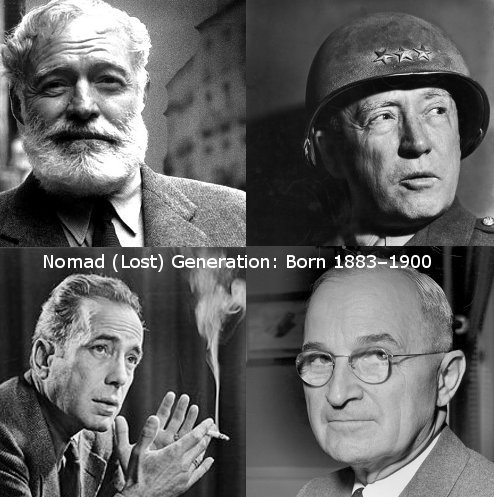

Nomad

Nomad generations are born and nurtured during a spiritual Awakening and grow up as unprotected children. Often seen as a nuisance by Artist and Prophet adults, Nomad children are left to find their own norms and are exposed to the world of adult dangers and anxieties at a young age. Consequently, Nomad children grow up fast and often engage in risky behavior.

Nomads come of age during an Unraveling as alienated and often cynical adults. However, their early exposure to the realities of adult life give them strong survival skills and a fierce independent streak that makes them well-suited to navigate the societal Unraveling that surrounds them.

In midlife, Nomads mellow into pragmatic and savvy leaders during a Crisis. Middle-aged Nomads make the personal sacrifices for the good of society that their elder Prophets weren’t willing to make during the Unraveling. The Nomads’ cunning and survival instincts make them well-suited to lead during a Fourth Turning. Many of America’s most memorable military, government, and business leaders were scrappy midlife Nomads (e.g. Generals Patton and Grant).

Nomads reach elderhood during a High. To compensate for the excessively risky decisions they made as young adults, aging Nomads shun risk and demand conformism from their peer group and especially from younger generations.

The Nomad’s main societal contributions are liberty, survival, and honor. Nomad generations have produced America’s greatest entrepreneurs and industrialists (Andrew Carnegie, Jeff Bezos), satirists (Mark Twain, Jon Stewart), and generals (Dwight Eisenhower, George Patton, George Washington). Nomad Generations include: Cavalier Generation (1618–1647), Liberty Generation (1724–1741), Gilded Generation (1822–1842), Lost Generation (1883–1900), Generation X (1961-1981).

Hero

Hero generations grow up as increasingly protected post-Awakening children. Prophet parents see their Hero children as instruments to fulfill their inner visions. Community and teamwork are instilled in Heroes at a young age. They are confident, ambitious, and optimistic about life, even in tough times.

Heroes enter young adulthood during a Crisis. Their youth, along with their orientation towards action and their ability to work well in teams, makes Heroes the go-to foot soldiers during a Crisis era. They are led by Nomads and revered by later generations for the sacrifices they make on the battlefield. Heroes enter midlife during a societal High, filled with confidence but also hubris from their early success during the Crisis; their penchant for taking on big projects can only be supported by the economic boom they experience during the High, which they naively believe will continue indefinitely. When the economy starts to sag during an Unraveling, younger generations are left holding the bag on faltering Hero-built programs and institutions.

Heroes are straightforward and polite; midlife Heroes become “defenders of a wholesome but conformist culture.” Technological advancement and institutional building are the main focuses of Hero leaders in Midlife, and they use this focus to create a well-ordered society. They eschew passionate and divisive ideology for a pragmatic approach to society and life, and when it comes to spirituality, either favor a pragmatic secularism or a non-charismatic, community-oriented mainline-type faith.

As they enter elderhood, Heroes begin receiving increasing scorn from younger Prophets for their lack of inner depth, spirituality, and passion. Consequently, Heroes “detach themselves from new cultural trends” while still maintaining an active role in public affairs.

The Hero generation’s main societal contributions are community, technology, and affluence.Hero generations have produced America’s greatest statesmen (James Madison, Thomas Jefferson) and societal builders (William Levitt). Throughout American history there have been three Hero Generations: The Glorious Generation (1648–1673), The Republican Generation (1742–1766), and the G.I. Generation (1901–1924).

Still Feeling Confused?

If you’re feeling confused about how this all goes together, let’s again take a look at how the turnings and generation types played out during out most recent cycle.

The Hero generation were young adults during our most recent Crisis: the Great Depression and WWII. Led by Nomads, they were the GIs who fought the war. After the war and the conclusion of the Fourth Turning, the Hero generation entered midlife and led society through a First Turning High. They led with a practical, civic-oriented, can-do spirit, and did big things like going to the moon. The Artist Generation (the Silent Generation) largely followed the Hero generation’s lead and acted as helpmates to it. These generations indulged their Prophet children, which made them a little self-absorbed. When the Prophet generation (the Baby Boomers) entered Young Adulthood, they led an Awakening (Second Turning), rebelling against the conformity and complacency of the Hero generation. As parents, the younger Boomer-Prophets and older Artist-Silents, raised a generation of latchkey kids, who became independent and cynical adults: the Nomad Gen X-ers. Because the Boomer-Prophet Awakening created a society that valued individualism and passionate ideology, the 80s and 90s were a time of Unraveling, with little consensus on shared values, fighting among interest groups, and stagnant civic progress. With a faltering economy, Hero-generated programs like LBJ’s Medicare have become difficult for the younger generations to sustain, while the Old Hero generation itself has largely passed on. Older Boomer and younger Gen X parents raised their kids in an over-protective way (helicopter parents), creating Millennial children, the next Hero generation.

Can Millennials Really Be the Next Hero Generation?

It’s difficult to identify prominent archetypal Millennials right now because they have not yet entered midlife, and thus most do not hold leadership positions. However, it is easy to find Millennials in sports, an arena in which their youth is not a barrier. Tim Tebow and Kevin Durant perfectly embody Millennials’ confidence and ambition, tempered with niceness, humility, and a good work ethic. And the OKC Thunder as a whole is a very Millennial team, filled with 20-something men who eschew indvidual glory to work together to win.

According to Strauss and Howe’s generational theory, the Millennial Generation (1982-2004) is our most recent Hero generation. They’ve gotten a lot of flack on this because, according to many columnists/opinion makers/sociologists, today’s young adult Millennials, aren’t displaying the qualities that you’d expect from a Hero generation. However, Howe would argue that it’s too early to judge whether Millennials will follow the Hero archetype; before the Depression/WWII Crisis, nobody thought the young G.I. generation was anything special either or had any idea that we’d later revere them as we do.

The more you look at it, the less of a stretch it becomes. The Millennial generation has weaknesses as every generation does, but they already display some classic Hero generation qualities: they’re very friendly, sensible, nice, and even-keeled, get along well with younger peers and older adults, are very peer and team-oriented, and prefer practical solutions over polarizing ideologies (more call themselves Independents than Republicans or Democrats). Millennials are also confident and ambitious goal-setters, and remain optimistic despite the downbeat economy; although they’ve been hit hard by the downturn, 9 in 10 still say “they earn enough money now to lead the kind of life they want, or that they expect to earn enough in the future.” Other insights to the true nature of Millennials’ values can be seen in the graph below, which is based on a study done this year:

John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers. Survey was conducted online Feb. 15-28 by Knowledge Networks, and included (1) 431 current junior, senior or graduate students at a four-year college in the fall of 2011; (2) 807 millennial workers (ages 21-32) who graduated from a four-year college and who are currently employed full time; (3) 230 Generation X workers (ages 33-48) who graduated from a four-year college and are currently employed full time; (4) 258 baby-boomer workers (ages 49-65) who graduated from a four-year college and who are currently employed full time.

While it is often said that Millennials are “idealistic,” this is perhaps a projection from Boomer parents who tried to instill this value in their kids; while Millennials do want meaningful jobs, they value “being financially secure” higher than other generations. They also place more importance on getting married, having kids, and being a leader in their community than Boomers and Gen X-ers do.

What the Strauss-Howe Generational Theory Tells Us About Manhood in America

“Every generation revolts against its fathers and makes friends with its grandfathers.” -Lewis Mumford

What I found most fascinating about the Strauss-Howe generational cycle theory was its effect on America’s notions of manhood and gender. Many people today have the mistaken assumption that all the hand-wringing and discussion lately about the state of manliness in America is something new and unprecedented. The reality is that America has experienced a few of these “Crises of Masculinity” before. During Colonial times, Americans had a tug-of-war on how American manhood would be defined: would it embodied by the European Genteel Patriarch or the more rugged Heroic Artisan?

After the Civil War and into the early 20th century, society began debating what manliness would mean in an industrialized world. As we noted in our post, Graphing Manliness, the number of books and pamphlets written about “manhood” and “manliness” increased dramatically during these years and then tapered off after WWI. Starting in 2000, after a century’s lull–the length of a saeculum–we once again started seeing a big uptick in books, articles, etc., written about manliness and manhood.

Howe and Strauss argue in their books that these recurring discussions about manhood and gender are to be expected. Each generational archetype has a different view on the subject:

- Prophet generations tend to feel more attached to their mothers and more distant from their fathers. When they come of age during an Awakening era, the feminine–associated with the resurgent emphasis on spirituality–is valued over the masculine, and distinctions between gender roles begin to narrow. Men become more “sensitive” and “in touch with their feminine side.”

- When Nomads come of age during an Unraveling, gender role distinctions narrow to their thinnest point in the generational cycle (think of the bobbed, brassy flappers of the 20s and the “gender is only a cultural construct” meme of the 80s). Nomad generations often revolt from the Prophet generation’s veneration of the feminine and begin finding ways to encourage gender distinctions in an increasingly gender neutral world. The quest for manhood is often seen as a futile attempt to recover honor in a world that no longer values honor. For Nomads, the only way for men to distinguish themselves from women is for the world to return to a “state of nature” in which a man’s primal, and sometimes violent traits, are more useful.

- Hero generations tend to feel more attached to their fathers than their mothers, as the masculine energies of war and civic involvement are revived during a Crisis, and gender roles begin to widen. The Crisis provides Hero men with the chance to perform distinctly masculine feats of courage and prove their manliness.

- When Artist generations come of age during a High era, the gap between gender roles are at their widest: the cultural ideal–even if not lived by the majority–is for men to take care of the public sphere, while women take care of the home. The masculine is favored over the feminine. Dissatisfied with the social arrangement, some Artists take steps towards narrowing the gender gap.

As I’ve interacted with men of all ages and read books by men on what it means to be a man, I’ve noticed how these characteristics play out in our current generations and the marked distinctions between how different generations view manliness:

Hero-G.I.

When you look at my grandfather’s G.I. generation, you see typical Hero views on gender. During the 1950s, when G.I.s entered midlife, distinctions between gender roles were at their widest compared to today. The cultural ideal consisted of a strong, authoritarian father who provided for his family, and a demure, feminine housewife who took care of the home.

Prophet-Boomer

Men in the Boomer generation generally live up to their Prophet archetype by viewing manliness in more spiritual terms…or as something not worth dwelling on at all. It’s interesting that the Mythopoetic men’s movement of the 80s and 90s–with its emphasis on the spiritual and emotional–was primarily a Boomer phenomenon. Men would go on retreats and bang on drums in the woods hoping to restore their “deep masculine,” while recognizing their “inner feminine.” Boomer authors like Sam Keene (Fire in the Belly) and Robert Millet (King, Magician, Warrior) published books that focused on helping men uncover and reconnect to their authentic and spiritual manhood. Some of the biggest Christian men’s ministries in America, like Promise Keepers, Men’s Fraternity, and Ransomed Heart Ministries, were started by Boomers as well.

Nomad-Gen X-ers

Gen X-ers generally approach manhood as consummate Nomads. Nomads often grew up as the products of divorce and as latchkey kids, and as a result they feel cynical about marriage and family. Many members of the “Men’s Rights Movement,” who often feel screwed by the system, particularly as it pertains to divorce court and child custody rulings, are Gen X-ers. In a very Nomadic move, there’s a small subset of Gen X men who have decided to “go their own way” and opt out of what they see as an unjust marriage system altogether.

Gen X Nomads are also sometimes pessimistic/angry about the future of men in general. Nihilism is not uncommon. Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club is a perfect example of Gen X masculinity: in order for manliness to mean anything, the world needs to go to pot first so men can use their innate masculine traits again. It’s very reminiscent of the works by fellow Nomad and manliness paragon, Ernest Hemingway.

This philosophy also shows up in the many popular blogs in the “Manosphere” that are written by Gen X men. Jack Donovan’s writings on manhood are a good example of the Nomad/Gen X view of manhood. Donovan doesn’t pull any punches when he talks about manhood. It’s raw and very Nietzschean. He, along with other Gen X men’s writers, argue that the only way to end the misandry and gender neutrality that we see in modern Western society is for society to collapse, as the tactical virtues of manliness are best demonstrated in a chaotic world. Of course, if the Strauss-Howe theory holds true, and we have already entered a Fourth Turning, they just might get their wish.

Hero-Millennials

When it comes to the Millennial Generation, they are in many ways taking their cues on manhood from their grandfather’s generation. Growing up, I always felt an affinity for my grandfather’s generation–whenever I could I wrote school papers on World War II and the Great Depression. One of the things Kate and I connected on when we first met, was that she had always felt drawn to that time period too (although she’s actually a year shy of being a true Millennial).

I held up my grandfather as the kind of man I wanted to be, and he was part of what inspired me to start the Art of Manliness. I wanted to create a men’s magazine with the kind of things I was interested in. The men’s magazines that were available didn’t resonate with me–they felt very 80s and 90s, very Generation X. No one has been more surprised than me that AoM has become such a large and popular blog. I didn’t know if any other guys my age felt the same way…but apparently, at least some do. This actually should not be that surprising in light of the Strauss-Howe generational theory, which says that each generation will most identify with the generation a full cycle distant from them–in the case of Millennials that’s the Hero-G.I.

What I see this mean for Millennial men is a desire to return to a simple, straightforward, non-angsty approach to being a man; they’re not so concerned about gender roles and manhood as something they need to get in touch with or analyze or are angry about; rather, it’s more like, “Yeah, I’m a man, and I like being a man. So how does a man live a good life?” Millennial men see being a man as their grandfathers did: don’t make a fuss about it, just be responsible, do the right thing, be competent, and get the job done. They want to live their life right and wantpractical advice on how to do that.

The recent reboot of Spiderman offers an interesting contrast between Gen X Spiderman (Tobey Maguire) and Millennial Spiderman (Andrew Garfield). Maguire’s Spiderman is the complete loner/loser/wallflower at his school–alienated from everyone and bullied. Garfield is bullied too, but he steps in to stop a bully from picking on someone else. And even that bully ends up showing he is a nice guy too deep down. And while Maguire has to wrestle with the responsibility of being a hero (at least in the second movie), Garfield has an easier time embracing his new role as one, perhaps because he already saw himself as having a duty to help others.

What’s really interesting is that Garfield embodies the Hero generational archetype off screen as well. While at Comic-Con before the film was released, he unmasked himself to a surprised crowd and gave a heartfelt speech of guileless sincerity about how much heroes really do matter, how Spiderman had taught him the importance of using one’s power for good, and that “doing the right thing,” is “worth it,” “worth the struggle…worth the pain:”

While Millennials do not want to go back to the strict gender roles of the 40s and 50s, they do seem to be questioning the more dogmatic ideas about gender neutrality they heard growing up, and searching for a way to honestly acknowledge the differences between men and women; they’re looking for a way for men and women to be seen as equal but not exactly the same. And they’re dipping their toes into traditionally gender-segregated activities more–at least playfully. Men have become interested in things like craftsmanship and woodworking, mustaches and beards, suits and ties, and DIY and survival skills, while more women have been getting into the DIY hobbies their grandmothers enjoyed like sewing, canning, and cooking.

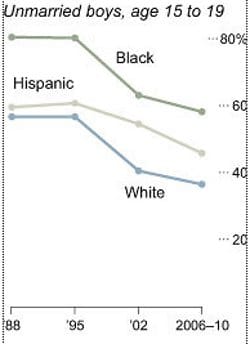

As the graph above showed, because Millennials were often raised in a more nurturing environment than their Gen X brethren, they are more optimistic about getting married and having kids. An embrace of commitment is a distinct Hero generation quality, and Millennials seem to approach relationships a little more traditionally than Gen X-ers did. For example, less teenage girls and boys are having sex (oral included), and the drop has been most pronounced in boys:

While in 1988, 60.4% of boys had had sex by the time they were 19, in 2010 that number was 42%. Why the large drop? While the number one reason boys give for abstaining has always been “morals and religion,” the second most popular reason had in previous surveys been “fear of getting a girl pregnant.” But in 2010, the second most common reason given by boys, was that they had not yet found the right person.

And when Lena Dunham, creator of HBO’s Girls offers up commentary like, “I heard so many of my friends saying, ‘Why can’t I have sex and feel nothing?’ It was amazing: that this was the new goal. There’s a biological reason why women feel about sex the way they do and men feel about sex the way they do. It’s not as simple as divesting yourself of your gender roles,” pundits take to wondering if such comments foretell a new direction for feminism.

Where will these trends lead? It’s hard to say. If the Strauss-Howe theory holds true, and the next decade foretells a deepening Crisis where masculine traits may once again be needed in an acute way, more traditional ideals of manhood may again take hold and the gap between the genders will widen once more….at least until the next generation of Prophets comes of age and rebels against their stodgy, sexist Millennial parents.

Regardless of what the future holds, the Strauss-Howe generational theory does explain that while each generation often feels passionate that they are “right” about what it means to be a man, their ideas of manhood have been shaped by other generations and the cycle of history. Which explains why many Nomad men don’t identify with the Mythopoetic idea of manhood championed by Boomers and can’t see themselves doing something like “Promise Keepers,” and why many Millennial men don’t identify with the cynical angst about manhood espoused by Gen X-ers. Of course, as aforementioned, in every generation there are those who lead the mood of that generation, those who follow it, and those who don’t identify with it at all and instead feel more of an affinity for the values of other generations.

In Conclusion

Despite the length of this post, there is still a ton more that could be covered about the Strauss-Howe generational theory of history. Generations and The Fourth Turning each weigh in at around 500 pages each. In attempting to give a brief-ish overview of the theory, much was left out, and what was left out may answer various questions that arose in your mind as you read this post.

Nevertheless, even if you take the time to plow through both books, you will still discover that the theory is far from airtight. There are plenty of holes to be found and objections to be raised. Furthermore, looking to it strictly as a guide to life and history, soon turns it into more of a squidgy horoscope chart than a historical/sociological theory. Those caveats aside, it is one of those things where taking the time to think through it, regardless of whether you end up embracing the theory completely, find truth in parts of it while rejecting others, or dismiss the theory wholesale, will very likely give you some fresh insights on life, history, and your place in it; it’s a fascinating prism through which to view the world.

So what do you think? Is there merit to the Strauss-Howe theory? If so, do you think that means that our current cultural/political funk will become a full on Crisis as we get deeper into a Fourth Turning? Or do you reject the idea of a historical/generational cycle? Did it provide any insight on how you and your friends and family view manhood? Lots to chew on here and I look forward to hearing your comments!

30 Days to a Better Man Day 1: Define Your Core Values

30 Days to a Better Man Day 1: Define Your Core Values Should a Man Be Inspired by History?

Should a Man Be Inspired by History? Are the Suburbs Killing Your Manhood?

Are the Suburbs Killing Your Manhood? Scarcity, Luxury, and Proving One’s Manhood

Scarcity, Luxury, and Proving One’s Manhood

No comments:

Post a Comment